This article originally appeared in a slightly different form in North Shore Sunday in February 2007.

When state senator Jarred Barrios tried to have the Fluffernutter sandwich banned from school lunches last year, he elicited howls of outrage, and for a good reason.

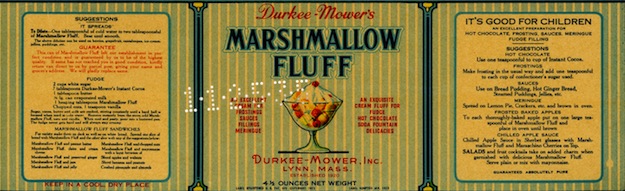

The Fluffernutter sandwich is more than a beloved memory of childhood, it’s a local tradition. Wikipedia lists it as an example of New England cuisine, alongside the noble baked bean and clam chowder. It’s even more local than that for the North Shore, because the active ingredient, Marshmallow Fluff, is made in Lynn by the Durkee-Mower company, which was started by two Swampscott High graduates, H. Allen Durkee and Fred L. Mower.

A little digging reveals that there’s more to Fluff than meets the eye, however. The Fluff people didn’t invent the Fluffernutter (just the name), our Fluff is not the only Marshmallow Fluff, and at one time, marshmallows were a health food. Take that, Senator Barrios!

Tastes terrible, cures everything

Our story begins with the humble marsh mallow, a flowering plant whose sap swells and forms a slippery gel when it is mixed with water.

Sound appetizing? The ancient Egyptians thought so; they mixed marsh mallow juice with honey to make special candy that was reserved for the pharaohs and the gods. The Roman scholar Pliny believed that a daily drink of marsh mallow juice would prevent all diseases, and if you were already sick when you got that news, it would also cure most illnesses. While not going to quite that extreme, doctors and healers prescribed the slimy juice to soothe sore throats and irritated skin well into the 20th century.

The change from health food to junk food occurred in Paris in the 1850s, when pharmacists began whipping up the juice with sugar and egg whites to make a light, foamy cure for sore throats. People liked the new product and started eating it like candy. By the end of the century, gelatin had replaced the marsh mallow juice, and the world began enjoying mallow-free marshmallows.

So, just as Grape-Nuts contains neither grapes nor nuts, Marshmallow Fluff is lacking a title ingredient.

In the early 20th century, a time when people believed any food could be improved by a white sauce, marshmallow frostings and sauces were popular dessert ingredients. Home cooks made their own marshmallow crême, either by mixing up the marshmallow ingredients from scratch or by melting down store-bought marshmallows and combining them with a sugar syrup. Neither method was quick or easy.

An idea whose time had come

Like many great discoveries, marshmallow crême may have occurred to several people at the same time. A New Jersey company called Limpert Brothers began selling a concoction called Marshmallow Fluff to soda fountain operators in 1913. At the same time the Whitman’s company (of Whitman’s Sampler fame) were selling something for home use called Marshmallow Whip.

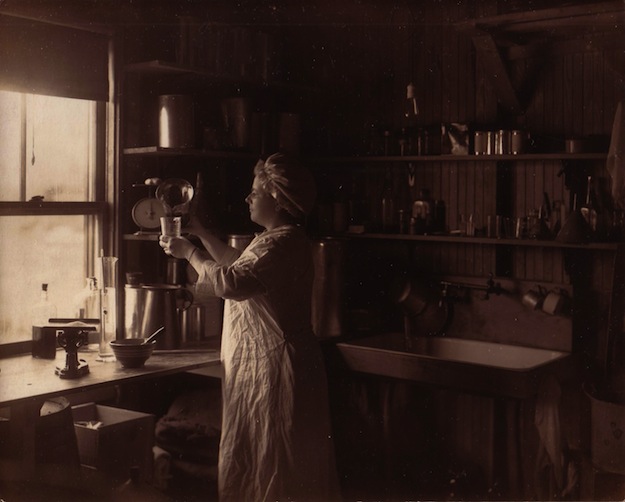

Enter the brother-and-sister team of Amory and Emma Curtis. Amory was a chemist and Emma was a marketing genius. In December 1913 they opened a factory in Melrose and began manufacturing their signature product, Snowflake Marshmallow Crême.

Amory Curtis had been a supplier of hardware and fruit extracts to soda fountains, and he may have encountered the Limpert Brothers’ version of Marshmallow Fluff in the course of that work. Whether or not he actually invented marshmallow crême, it’s clear that marketing was the magic ingredient that made Snowflake Marshmallow Crême the first commercially successful marshmallow crême sold for home use.

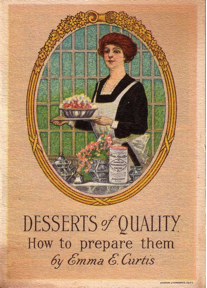

The Curtises pitched their product aggressively to grocers, sending them free cans so they could provide samples to customers. Emma also developed and tested recipes at home, and the family ate marshmallows in some form at almost every meal: thinned marshmallow crême on breakfast cereal, marshmallow dressing on salad, marshmallow sauce on dessert. Emma printed up little leaflets with these recipes and sent them out for free to customers. In 1915 Snowflake Marshmallow Crême, by then a nationally distributed product, won a gold medal at the Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco.

The eureka moment

It was only a matter of time before someone would think of putting marshmallow crême in a sandwich. Early leaflets recommended spreading Snowflake Marshmallow Crême on crackers and topping it with chopped nuts and olives, or making tea sandwiches of butter and marshmallow fluff and cutting them into triangles. These are clearly dead-ends on the evolutionary tree, the Fluffernutter equivalent of Neanderthal man.

Then it happened: A Snowflake recipe leaflet Emma published in 1918 contains a recipe for a “Liberty Sandwich”: peanut butter and Snowflake Marshmallow Crême on “war bread,” which was bread that included oats, barley, or corn to conserve wheat. Since the recipe didn’t appear in the 1916 version of the leaflet, we can date the invention of the ur-Fluffernutter sandwich fairly accurately: It appeared during World War I, a time when Americans were urged to go without meat once a week. “Liberty sandwich” originally referred to hamburgers; it was a patriotic renaming of a product whose name evoked the enemy (think “freedom fries.”) Perhaps Emma dreamed up her sandwich to fill the void on a grim Meatless Monday when the war bread wasn’t looking too good on its own.

The Durkee-Mower company wasn’t even founded until two years later, and company treasurer Jon Durkee, the grandson of the founder, didn’t know too much about the origins of the Fluffernutter. “The sandwich itself was around from the beginning,” he says. “It just didn’t have the name Fluffernutter stuck to it. The name came up in roughly 1960. We had an advertising agency, and they came up with the name.”

Durkee says his family didn’t test recipes at home when he was growing up, but he occasionally tries out a new idea on his kids. “We are always out trying to come up with new fudge recipes,” he says, “and we came up with a cheesecake recipe years ago, which is on our website—that was something we inflicted on our family. That was fun. We made a peanut brittle recipe too.”

Competition

While Emma was perfecting her recipes in her home laboratory, Archibald Query of Somerville was whipping up batches of white stuff in his home kitchen. World War I forced the Curtises to raise their prices, due to sugar shortages, but it put Query out of business altogether. After the war, he briefly formed a partnership with Durkee and Mower, and in 1920 the pair bought him out and formed the eponymous Durkee-Mower Company.

The ingredients for the Fluffernutter came together quickly after that. Peanut butter had been around since the mid-1890s, having been invented as a protein supplement for people with no teeth. The original product was a gritty paste that tended to separate into oil and a peanutty sludge, but for some reason people liked it, and its popularity got a boost from the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. In 1922, Joseph L. Rosefeld figured out how to churn peanut butter to make it smooth and spreadable, and the ingredients for a great sandwich were in place.

As Marshmallow Fluff became more popular, a problem cropped up: Durkee-Mower was using a name that the Limpert Brothers had trademarked in 1910. “They were in New Jersey, and we were in New England, and you couldn’t do an internet search and find out about trade names back then,” says Durkee. “They had prior use of the name, although it’s a slightly different product. Theirs was more for ice cream topping. It’s thicker, more fluid.” In an unusual arrangement, the two companies agreed to share the name and make sure that the products don’t overlap. Limpert Brothers sell their products to ice cream shops and soda fountains, while Fluff is a retail product, so there was little conflict. To keep it that way, the agreement states that Fluff cannot be sold in containers larger than 1 pound, except in New England, where Durkee-Mower does sell a larger size to wholesalers for resale to schools and other institutions.

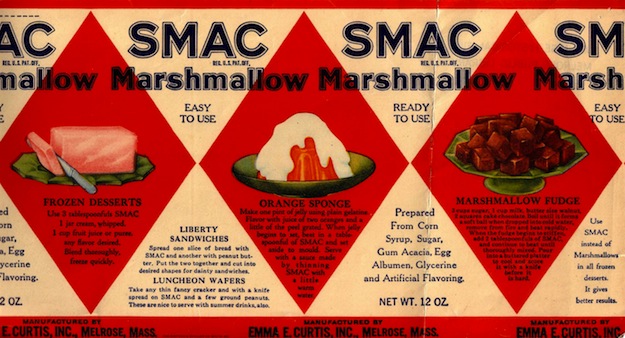

The Curtises created their own whipped marshmallow crême, which they called SMAC, in 1922, and it was popular in this region for years. The SMAC label, adorned with red and white diamonds, proudly bore the recipe for the Liberty Sandwich along with other marshmallow treats, mainly puddings and sauces. Bailey’s, the venerable Boston chain of ice cream shops, used it on their sundaes, and long after the Curtis factory shut its doors (it burned down in 1962), Amory Curtis would whip up a batch of SMAC every week just for Bailey’s.

Continuing the tradition

Although he is the grandson of the founder of the company, Durkee admits that he didn’t eat many Fluffernutters growing up. “I wasn’t a big peanut butter fan,” he says. And the next generation? One of his three kids shares his aversion to peanut butter, but another eats them “a lot.”

While the canonical Fluffernutter sandwich of creamy peanut butter and Fluff on squishy white bread may make nutritionists shake their heads it’s easy to think of a healthier version. Made on multigrain bread, with that “natural” peanut butter that has to be stirred before use, it would also be a lot like the original Liberty Sandwich. No doubt Emma Curtis would approve.

And with that combination of whole grains and history, maybe even Jarred Barrios would learn to like it.

I am the Grandson and Great Nephew of the founders of Limpert Bros. John.H.Limpert and Gregory Limpert.

Limpert Bros.did not invent Marshmellow fluff ,but did copyright the name and held its exclusive rights to the wholesale trade,While Durkee-Mower had the retail rights .This is why you see Marshmellow Fluff in Supermarkets under Durkee’s Brand and not Limperts.

A rare situation where two companies share the rights to the same Famous product.